Human Risk Management: Safety-I vs. Safety-II in Cybersecurity

The Uncomfortable Truth About Human Risk in Cybersecurity

Depending on the study, between 60% and 95% of all cyber incidents are caused by human behavior. This figure is repeated at every security conference, cited in every presentation, and serves as justification for countless security awareness training programs. Yet this statistic raises a much more important question: How do we actually deal with this human risk?

After it-sa 2025 in Nuremberg, where CISOs and security professionals from across the DACH region gathered to evaluate the latest solutions, it's time for a critical assessment. The exhibition halls were packed with vendors promising to manage "human risk." But upon closer examination, a fundamental difference in approaches emerges that can determine the success or failure of your security strategy.

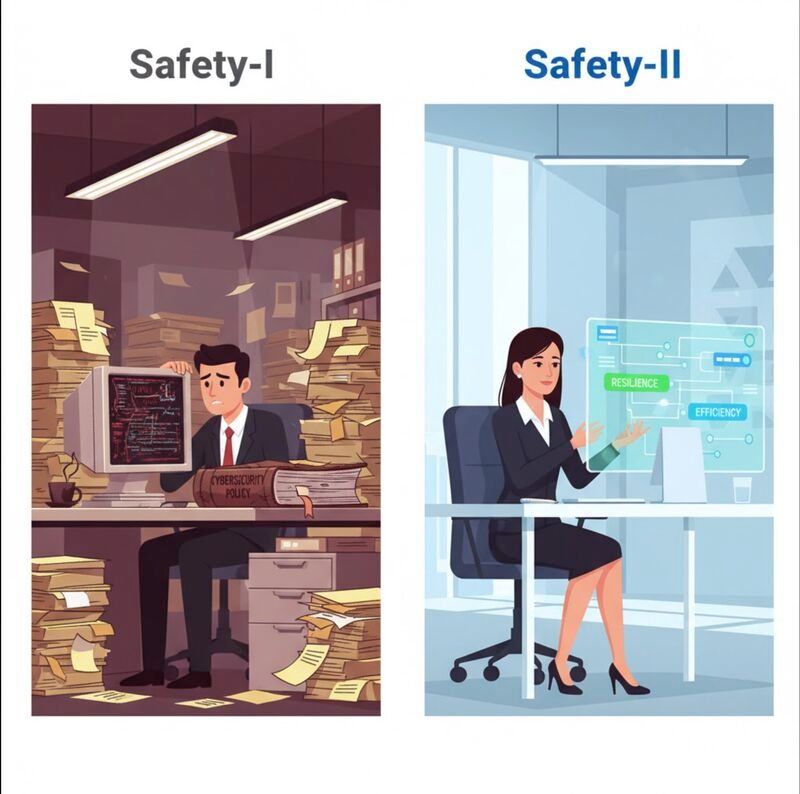

Safety-I vs. Safety-II: Two Fundamentally Different Philosophies

To understand the various approaches in human risk management, we need to examine two concepts from safety research: Safety-I and Safety-II.

Safety-I: The Traditional Approach

Safety-I defines security as the absence of failures. In this paradigm, safety means that as little as possible goes wrong. The focus is on:

- Identifying errors and vulnerabilities

- Analyzing past incidents

- Assigning blame and corrective measures

- Reducing error rates through training and sanctions

- Measuring compliance metrics

In the context of cybersecurity, Safety-I typically manifests through:

- Phishing simulations that measure click rates

- Mandatory security awareness training

- Reporting employees who click on simulated phishing emails

- Training and "re-education" for repeat offenders

- KPIs like "percentage of employees who don't click on phishing emails"

Safety-II: The Systemic Approach

Safety-II defines security as the ability to succeed. Here, safety doesn't mean the absence of errors, but the system's ability to function successfully even under varying conditions. The focus is on:

- Understanding what normally goes right

- Building resilience and adaptability

- Systemic thinking instead of individual blame

- Reducing the consequences of errors

- Creating conditions that enable safety

In the cybersecurity context, Safety-II means:

- Defense-in-depth architectures that work even when humans make mistakes

- Zero-trust principles that assume errors will happen

- Automatic incident response systems

- Segmentation and least-privilege concepts

- Redundant security controls at different levels

The Critical Question for Every Security Vendor

When you as a CISO or security professional face the decision to invest in a human risk management solution, you should ask this central question:

"Does your tool only reduce the click rate in the next phishing simulation (Safety-I), or does it reduce the actual, systemic probability that a click will have catastrophic consequences at all (Safety-II)?"

This question separates managing the blame narrative from building genuine, systemic resilience.

Why Is This Distinction So Important?

Imagine this scenario: After months of training and countless phishing simulations, your company has reduced the click rate from 30% to 5%. An impressive success that you can proudly present.

But then it happens: An employee from the remaining 5% clicks on a sophisticated spear-phishing email. The attacker gains access to the network. What happens now?

- In the Safety-I approach: The employee is identified, trained, possibly sanctioned. Blame is assigned. The system has "failed" because a human made a mistake.

- In the Safety-II approach: The system kicks in. Multi-factor authentication prevents direct access. Network segmentation limits lateral movement. Anomaly detection raises alerts. Automatic incident response isolates affected systems. Damage is minimized or completely prevented, independent of the human error.

The Limits of Behavior Engineering

Focusing on behavior change as the primary security measure has fundamental limitations:

1. Humans Are Not Perfectly Programmable Machines

Even with the best training, humans will make mistakes. Stress, time pressure, distraction, and the increasing sophistication of attacks make it impossible to achieve a zero error rate.

2. Attackers Adapt

While you train your employees against known phishing patterns, attackers develop new techniques. Deepfakes, AI-generated texts, and highly personalized attacks make it increasingly difficult to distinguish legitimate from malicious messages.

3. The Blame Narrative Damages Security Culture

When every incident leads to a search for someone to blame, employees will hesitate to report suspicious cases. A culture of fear is the opposite of a resilient security culture.

4. Budget Allocation Becomes Inefficient

Endless training, simulations, and awareness campaigns tie up resources that could flow into systemic improvements that actually reduce the impact of incidents.

The Path to True Cyber Resilience

A mature cybersecurity strategy combines both approaches but emphasizes systemic resilience:

1. Accept Human Errors as a System Premise

Design your security architecture assuming that humans will make mistakes. Ask yourself: "What happens if an employee clicks on a phishing link?" and build appropriate protective mechanisms.

2. Implement Zero-Trust Architectures

Don't automatically trust users within your network. Every access should be verified, authorized, and logged, regardless of whether the request comes from inside or outside the network.

3. Use Automation and Orchestration

Automated response mechanisms react faster and more consistently than humans. Security Orchestration, Automation and Response (SOAR) platforms can drastically reduce the time between detection and response.

4. Build Redundancy and Segmentation

No single control should be the only protection against a threat. Network segmentation prevents a compromise of one system from endangering the entire network.

5. Foster a Positive Security Culture

Instead of blame assignment, incidents should be viewed as learning opportunities. Encourage employees to report suspicious activities without fear of consequences.

6. Awareness Yes, But Context-Based

Security awareness training should be understood not as a primary line of defense, but as a complementary measure. Make it relevant, practical, and integrated into daily work.

What Counts Before the Board

When, despite all measures, a serious incident occurs, you will have to be accountable to the board or executive management. In that moment, what counts is:

Not: "We had a click rate of only 5% in our phishing simulations."

But: "Despite the human error, our systemic controls worked. Access was blocked by MFA, the anomaly was detected within minutes, affected systems were automatically isolated, and potential damage was limited to a minimum. Here is our post-incident report and the improvements already implemented."

The Perspective After it-sa 2025

The question that now arises: Which approach dominated at it-sa? Did vendors primarily present tools for behavior monitoring and awareness measurement, or was the focus on systemic solutions that build resilience through technical controls?

For decision-makers in German medium-sized businesses, this distinction is particularly relevant. With limited budgets and resources, investments in cybersecurity must deliver maximum value. Focusing on systemic resilience offers:

- Scalability: Once implemented, technical controls protect permanently without continuous behavioral interventions

- Measurability: Technical controls can be objectively tested and validated

- Compliance: Many frameworks (BSI IT-Grundschutz, ISO 27001, NIS2) require technical controls

- Cost-effectiveness: More economical in the long term than endless training programs

Conclusion: Time for a Paradigm Shift

The cybersecurity industry must move away from its obsessive focus on human misbehavior and instead design systems that are robust against human errors. This doesn't mean security awareness is unimportant, but that it must be put in the right context: as a supporting, not primary, security measure.

The crucial question when evaluating any human risk management solution should be: Does this solution build genuine resilience, or does it just manage the blame narrative?

Your investment decisions should prioritize tools and strategies that reduce the systemic probability of catastrophic consequences, not just the click rate in the next simulation.

In a world where human errors are inevitable, your system's ability to remain secure despite these errors is the true measure of cybersecurity excellence.

What is your perspective? How do you prioritize between behavior control and systemic resilience in your organization? What experiences have you had with both approaches?